The release of a guide to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan is receiving very poor media coverage.

This headline – “Basin Authority holds its first public meeting” - is entirely misleading. The Authority had numerous meeting with stakeholders including water users, irrigation groups, farmers groups, local councils, and anyone else who could claim and interest for the past two years. There should be no surprises.

Another

here – “As many as 130,000 jobs could be lost because of reduced water allocations in Victoria's fruit bowl region under the Murray-Darling Basin plan, a farmer says” That’s right. A farmer says so, therefore it must be true.

This is a week the farming lobby has spent years preparing for, and they are basking the attention.

The further problem which is completely overlooked by the media, is that while the reductions in rights to take water are ‘up to 37%’ that means that most reduction in most rivers are ‘between zero and 37%’.

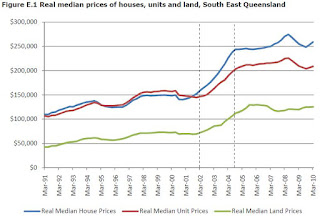

Let’s not also forget the fact that these are reductions of paper rights, not volume taken. There would be very few water users whose volume taken matches the volume of their rights due to variability and recent dry conditions. The graph below shows that recent rainfall conditions are below historical averages, although this is not uncommon in the long term.

What is missing from this mainstream media nonsense is any actual thought about the reason the plan was developed in the first place. Simply put, there are more rights to take water ‘on paper’ than there is water in the system. This leads to both downstream water users suffering at the expense of upstream users, and environmental areas suffering due to upstream water users. When downstream environmental assets, such as wetlands, receive water, the water also flows through to downstream users.

There is even the possibility that the next five years more water will be used by irrigators than the past five years, even with the Basin Plan, simply because of rainfall variability. The percentage figures are based on long run averages, which are a distant memory for many people in the Basin.

Imagine I give you a piece of paper that allows you to take 100ML/annum of water from a particular reach of a river. The river flow is highly variable and because of this you get 60ML one year, zero the next three, 100ML the next, then 25ML. You average 31ML. Then, you get told the stream is overallocated and you are getting cut 37%, so that your allocation is now 63ML. If we had the previous six years again the impact would have only occurred in one year - the cut would take your five year average from 31ML to 25ML – a 20% decline in average use, and a once in five year impact.

If over the next 5 years you can take 63ML, zero, 25ML, 50ML, 5ML and 60ML, you might end up with even more water on average – 34ML/a instead of 31ML/a – despite the theoretical cut to you water right.

In South Australia for example, irrigators have only been able to access 10% or less of their water rights over the past 5 years or so. If the Basin as a whole shares the water more equitably, these irrigators may be able to use 63% of their previous water allocation – a 37% cut on paper, but a 600% increase in real water use compared to the past 5 years.

Even the MDBA itself showed just how low actual water use is compared to these theoretical baseline figures from which reductions are calculated. The graph below is from page 130 of the Guide and shows that the average water use since 2002-03 is equal to their most ambitious reduction scenario.

My point is, people are taking the cuts as real water then multiplying impacts to flow on industries then getting bigger and bigger impacts that border on ridiculous. These complementary agricultural industries are clearly already adjusted to any proposed cutbacks.

The only person to present any figures on the media circus is economist Quentin Grafton. He makes his case that

farmers are exaggerating losses as follows:

"In 2000-2001, the gross value of irrigated agricultural production was just over $5 billion, and they used surface water of about 10,500 gigalitres in that particular year," he says.

"Fast forward to 2007-08, 70 per cent reduction in surface water use, guess what happened to the gross value of irrigated agricultural production? It changed by less than 1 per cent."

Not only are impacts greatly overstated but water users will generally be compensated for their theoretical water loss at market prices for water – whether the water exists or not.

Historically most water rights are a gift from the State to landholders. They have generally earned a good living from these gifts, and now that the government has realised that too many were granted, they are going to pay to buy them back.

While I’m on the water bandwagon, some people are taking the chance to have a dig at cotton and rice growers for their water consumption. What they need to understand is that while Australia is a dry continent, we are characterised by variability of rainfall. Some years it floods and to make use of the water you need a thirsty annual crop. That’s why the virtual desert regions south of St George are cotton areas, even though this intuitively seems bizarre.